After being forgotten for nearly 47 years, three high resolution images taken by the Lunar Orbiter II spacecraft have been rediscovered by the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project (LOIRP). It is unlikely that anyone has seen these images since they were sent back to Earth. Indeed, it is unlikely that very many people saw them at that time either.

The three high resolution images were taken along with a medium resolution image on 23 November 1966 at 17:05:39 GMT. The center point of the images was 26.94 West Longitude, 3.196 degrees North Latitude. The images were taken at an altitude of 43.6 km and the image resolution is 0.93 meters.

We recently came across these three images (#2159) and noticed that they do not appear online at the LPI Lunar Orbiter database. Only the medium resolution image gets mentioned at LPI.

These three images were retrieved from original Lunar Orbiter program analog data tapes yet they appear nowhere in NASA’s publications. They do appear on microfilm archives at LOIRP and are mentioned in a simple data log online at LPI. LOIRP has a more extensive computer printout of this data that shows more detail about the images – but not the images themselves.

Unless someone happened to be looking through this microfilm collection (LOIRP has the only extant copy) then it is pretty safe to assume that no one has actually seen these images since a technician saw them on a TV monitor in 1966.

– Left Image [larger] [Raw TIFF – very large]

– Middle Image [larger] [Raw TIFF – very large]

– Right Image [larger] [Raw TIFF – very large]

Note: These three images actually comprise portions of a single high resolution image but these high resolution images were traditionally divided up and numbered in three parts by the Lunar Orbiter program.

The Lunar Orbiter project was rather well documented. Indeed, it is this documentation that allowed the LOIRP to figure out what images are located on which tape, but also how to repair and replace hardware on our 50 year old tape drives. In the course of retrieving images from the original analog data tapes we have come across a number of images – some only partial images – that are not included in formal program documentation or listed in LPI or USGS databases.

We have a working theory as to why these images have been forgotten for the past 47 years. There were three ground stations involved in retrieving data from Lunar Orbiters – Woomera, Australia, Madrid, Spain, and Goldstone, California. There is some overlap due to planetary geometry such that images were often recorded by more than one ground station.

When the spacecraft was playing back its imagery there was only one chance to get the data since it was really not feasible (or advisable) to rewind the film and re-scan and retransmit – since there was no ability to store these images electronically on the spacecraft. So, if one or more ground stations did not record data the first time it was sent, there was no second chance.

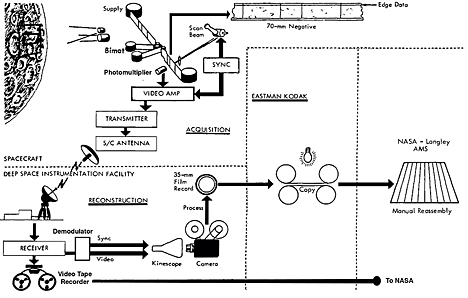

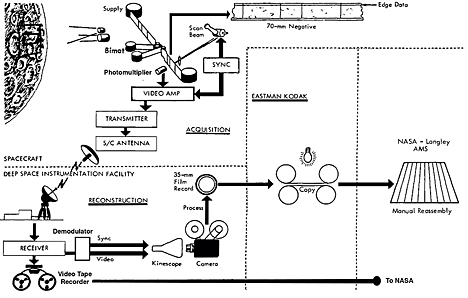

How data was sent back to Earth and stored as photographs and data tapes. Click on image to enlarge.

Lunar Orbiters shot their images on 70mm SO-243 photographic film. The film was developed aboard the spacecraft, scanned and sent back to Earth as analog data. One data stream demodulated the image and sent it to a high resolution kinescope (TV screen) where the image on the screen was photographed as a photographic positive. Those photographs were subsequently re-photographed to create a negative, then stitched together and photographed again to create photographic prints used for the requirements of the program.

The data was also sent to analog videotape machines where it was recorded for posterity. Given that the data stored on the analog tapes was scanned directly from the film in lunar orbit and recorded as data on magnetic tape these images were of much higher quality than the photos taken off of the kinescope and re-photographed multiple times. These data tapes were used sparingly to digitize small “chits” that were run through computer programs to measure the height of rocks on the surface and the slope of the surface within the landing ellipses chosen based upon looking at the photographic prints. These computer measurements were done to validate the safety of the landing area as this was difficult to do using just the film record.

The photographic process of capturing kinescope images continued as long as data was being received. But the data tapes had to be changed out after several images had been recorded. However, the spacecraft playback continued while the technicians changed out the tapes – and that process took a few minutes. During the time that the tape was being changed out analog data was not being recorded by that ground station – but it might be recorded by another during the overlap period. Then again it might not.

The way that the images came down involved the transmission of a medium resolution version of an area followed by high resolution images of that area. So, tape changeout tended to happen as the medium resolution image came in. That way, at most, a small portion of the medium resolution image was not recorded on tape. But the photographs of the images appearing on the kinescope continued nonstop – hence the presence of these images on our microfilm collection (these microfilm images were originally given to Dennis Wingo from then fellow student Eric Dahlstrom in 1989 after being purchased at surplus from NASA GSFC). The high resolution images were what most interested the Lunar Orbiter project team – the medium resolution images served to place the high resolution images into context.

Detailed information on image 2159. Click on image to enlarge.

Detailed information on image 2159. Click on image to enlarge.

You might wonder why each ground station did not have more than one tape drive. Well, given the expense of these drives, they were lucky just to have one at all three ground stations. Most of the time the images were captured without incident, often by more than one ground station.

Sometimes flaws in the film or glitches on the playback system on the spacecraft would cause flawed images to be sent back. Those flawed images were usually of partial use. That said these flawed images were cataloged as part of the detailed program documentation. As good as these folks were with documenting things, some stuff fell through the cracks.

In the case of image 2159 we think that there was some problem with retrieving the image and that it was designated as having a flaw – but that fact never made it into program documentation. The images were on microfilm that were derived from the data tapes. But the high resolution imagery for 2159 was not printed out and assembled into prints for use by the project team. When we retrieved this high resolution image we did encounter some problems that necessitated some hand assembly. This could well have been part of the problem experienced in 1966.

Regardless of the cause(s) we have retrieved the his resolution imagery and have made it public. Over the next few weeks we’ll be releasing some other images which may have suffered a similar fate.

The Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project (LOIRP) is located at the NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, CA. Funding and support for this project has been provided by NASA Headquarters, NASA Lunar Science Institute, NASA Ames Research Center, SkyCorp Inc., and SpaceRef Interactive Inc.

For more information on the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project (LOIRP) visit https://moonviews.wpenginepowered.com

For information on NASA’s Lunar Science Institute visit http://lunarscience.arc.nasa.gov/

Dennis Wingo: We are still on stand down until the tape drive head gets back from the shop. It was delivered to Videomagnetics today so hopefully it will be back here before the end of next week. While we wait, Austin Epps and Jacob Gold (who has joined us as one of our student interns this summer) are catching up on the back end processing of the images. Jacob has over 3,000 framelets to number right now!

Dennis Wingo: We are still on stand down until the tape drive head gets back from the shop. It was delivered to Videomagnetics today so hopefully it will be back here before the end of next week. While we wait, Austin Epps and Jacob Gold (who has joined us as one of our student interns this summer) are catching up on the back end processing of the images. Jacob has over 3,000 framelets to number right now!