To Behold the Moon: The Lunar Orbiter Project. Chapter 10, Spaceflight Revolution, NASA SP-4308

To Behold the Moon: The Lunar Orbiter Project. Chapter 10, Spaceflight Revolution, NASA SP-4308

But, Cliff, you said we weren’t going to improvise like this….

But, listen to what I say now! We’ve worked out the numbers. It’s worth the risk.

– Conversation between Boeing engineer project manager Robert J. Helberg and Clifford H. Nelson, head of Langley’s Lunar Orbiter Project Office, concerning a change in the mission plan for Lunar Orbiter 1.

The bold plan for an Apollo mission based on LOR held the promise of landing on the moon by 1969, but it presented many daunting technical difficulties. Before NASA could dare attempt any type of lunar landing, it had to learn a great deal more about the destination. Although no one believed that the moon was made of green cheese, some lunar theories of the early 1960s seemed equally fantastic. One theory suggested that the moon was covered by a layer of dust perhaps 50 feet thick. If this were true, no spacecraft would be able to safely land on or take off from the lunar surface. Another theory claimed that the moon’s dust was not nearly so thick but that it possessed an electrostatic charge that would cause it to stick to the windows of the lunar landing vehicle, thus making it impossible for the astronauts to see out as they landed. Cornell University astronomer Thomas Gold warned that the moon might even be composed of a spongy material that would crumble upon impact.1

At Langley, Dr. Leonard Roberts, a British mathematician in Clint Brown’s Theoretical Mechanics Division, pondered the riddle of the lunar [312] surface and drew an equally pessimistic conclusion. Roberts speculated that because the moon was millions of years old and had been constantly bombarded without the protection of an atmosphere, its surface was most likely so soft that any vehicle attempting to land on it would sink and be buried as if it had landed in quicksand. After the president’s commitment to a manned lunar landing in 1961, Roberts began an extensive three year research program to show just what would happen if an exhaust rocket blasted into a surface of very thick powdered sand. His analysis indicated that an incoming rocket would throw up a mountain of sand, thus creating a big rim all the way around the outside of the landed spacecraft. Once the spacecraft settled, this huge bordering volume of sand would collapse, completely engulf the spacecraft, and kill its occupants.2

Telescopes revealed little about the nature of the lunar surface. Not even the latest, most powerful optical instruments could see through the earth’s atmosphere well enough to resolve the moon’s detailed surface features. Even an object the size of a football stadium would not show up on a telescopic photograph, and enlarging the photograph would only increase the blur. To separate fact from fiction and obtain the necessary information about the craters, crevices, and jagged rocks on the lunar surface, NASA would have to send out automated probes to take a closer look.

The first of these probes took off for the moon in January 1962 as part of a NASA project known as Ranger. A small 800-pound spacecraft was to make a “hard landing,” crashing to its destruction on the moon. Before Ranger crashed, however, its on-board multiple television camera payload was to send back close views of the surface -views far more detailed than any captured by a telescope. Sadly, the first six Ranger probes were not successful. Malfunctions of the booster or failures of the launch-vehicle guidance system plagued the first three attempts; malfunctions of the spacecraft itself hampered the fourth and fifth probes; and the primary experiment could not take place during the sixth Ranger attempt because the television equipment would not transmit. Although these incomplete missions did provide some extremely valuable high-resolution photographs, as well as some significant data on the performance of Ranger’s systems, in total the highly publicized record of failures embarrassed NASA and demoralized the Ranger project managers at JPL. Fortunately, the last three Ranger flights in 1964 and 1965 were successful. These flights showed that a lunar landing was possible, but the site would have to be carefully chosen to avoid craters and big boulders.3

JPL managed a follow-on project to Ranger known as Surveyor. Despite failures and serious schedule delays, between May 1966 and January 1968, six Surveyor spacecraft made successful soft landings at predetermined points on the lunar surface. From the touchdown dynamics, surface-bearing strength measurements, and eye-level television scanning of the local surface conditions, NASA learned that the moon could easily support the impact and the weight of a small lander. Originally, NASA also [313] planned for (and Congress had authorized) a second type of Surveyor spacecraft, which instead of making a soft landing on the moon, was to be equipped for high-resolution stereoscopic film photography of the moon’s surface from lunar orbit and for instrumented measurements of the lunar environment. However, this second Surveyor or “Surveyor Orbiter” did not materialize. The staff and facilities of JPL were already overburdened with the responsibilities for Ranger and “Surveyor Lander”; they simply could not take on another major spaceflight project.4

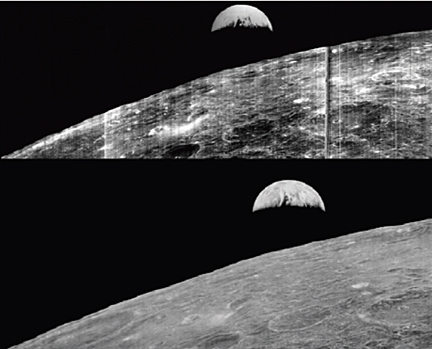

In 1963, NASA scrapped its plans for a Surveyor Orbiter and turned its attention to a lunar orbiter project that would not use the Surveyor spacecraft system or the Surveyor launch vehicle, Centaur. Lunar Orbiter would have a new spacecraft and use the Atlas-Agena D to launch it into space. Unlike the preceding unmanned lunar probes, which were originally designed for general scientific study, Lunar Orbiter was conceived after a manned lunar landing became a national commitment. The project goal from the start was to support the Apollo mission. Specifically, Lunar Orbiter was designed to provide information on the lunar surface conditions most relevant to a spacecraft landing. This meant, among other things, that its camera had to be sensitive enough to capture subtle slopes and minor protuberances and depressions over a broad area of the moon’s front side. As an early working group on the requirements of the lunar photographic mission had determined, Lunar Orbiter had to allow the identification of 45-meter objects over the entire facing surface of the moon, 4.5-meter objects in the “Apollo zone of interest,” and 1.2-meter objects in all the proposed landing areas.5

Five Lunar Orbiter missions took place. The first launch occurred in August 1966 within two months of the initial target date. The next four Lunar Orbiters were launched on schedule; the final mission was completed in August 1967, barely a year after the first launch. NASA had planned five flights because mission reliability studies had indicated that five might be necessary to achieve even one success. However, all five Lunar Orbiters were successful, and the prime objective of the project, which was to photograph in detail all the proposed landing sites, was met in three missions. This meant that the last two flights could be devoted to photographic exploration of the rest of the lunar surface for more general scientific purposes. The final cost of the program was not slight: it totaled $163 million, which was more than twice the original estimate of $77 million. That increase, however, compares favorably with the escalation in the price of similar projects, such as Surveyor, which had an estimated cost of $125 million and a final cost of $469 million.

In retrospect, Lunar Orbiter must be, and rightfully has been, regarded as an unqualified success. For the people and institutions responsible, the project proved to be an overwhelmingly positive learning experience on which greater capabilities and ambitions were built. For both the prime contractor, the Boeing Company, a world leader in the building of….

The most successful of the pre-Apollo probes, Lunar Orbiter mapped the equatorial regions of the moon and gave NASA the data it needed to pinpoint ideal landing spots.

Continue reading “To Behold the Moon: The Lunar Orbiter Project”

Research led by astrophysicists at the University of Warwick has resolved a 40 year old problem with observations of turbulence in the solar wind first made by the probe Mariner Five. The research resolves an issue with what is by far the largest and most interesting natural turbulence lab accessible to researchers today.

Research led by astrophysicists at the University of Warwick has resolved a 40 year old problem with observations of turbulence in the solar wind first made by the probe Mariner Five. The research resolves an issue with what is by far the largest and most interesting natural turbulence lab accessible to researchers today.

Bruce K. Byers, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C. 1977, NASA TM X-3487

Bruce K. Byers, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C. 1977, NASA TM X-3487

To Behold the Moon: The Lunar Orbiter Project. Chapter 10, Spaceflight Revolution,

To Behold the Moon: The Lunar Orbiter Project. Chapter 10, Spaceflight Revolution,